This

past weekend, I published something very different from my other works. With

Halloween approaching, I decided to write and publish a horror story. That may

sound about as far from my usual military historical fiction as one can get.

But perhaps not.

Why

would I choose to write horror? I have been fascinated by the genre since I was

a child. My mother loved horror films, and our whole family went to the movies

together. Like Cosby’s Fat Albert and his buddies, I used to crouch behind the

seats and peer between them to watch the scary scenes. I remember watching Lon

Chaney Jr.’s face change from that of a man to that of a wolf through

time-lapse photography. I recall the mummy’s ghost carrying Ramsay Ames into

the swamp until they disappeared. I saw

David Carradine, in my opinion the best Dracula, turn to dust when caught by

the sunlight. We also saw all the horror anthologies like Frankenstein Meets the Wolfman and Abbot and Costello Meet Frankenstein. A latecomer to the scene was

The Creature From the Black Lagoon.

About

the time I became a teenager, an amazing comic book series (actually short

graphic novels) called Tales from the

Crypt appeared on the market. The

werewolves, vampires, and other monsters in these books were convincingly

drawn, and the stories were spine tingling. Unfortunately (for fans of the

series) someone convinced the publisher that he was contributing to juvenile

delinquency, so he pulled the plug on the books. Some years later, the title

was revived on a TV series.

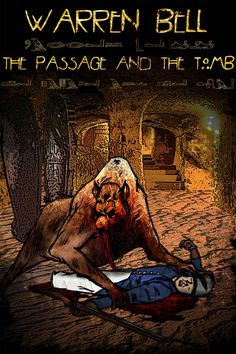

My

new story, The Passage and the Tomb: A Tale of Ancient Horror, takes place in Egypt in the early 1800s. My characters are soldiers

and scientists from Napoleon’s invading army. Okay, so I can’t really suppress

the historical novelist in me. Napoleon’s savants studied and documented the

ancient Egyptian civilization for several years. They essentially invented

Egyptology. What better foils to confront an ancient evil than the explorers

who opened up the longest lasting civilization to the world?

Inadvertently,

my characters free a 4,000-year-old werewolf who had been entombed alive by the

ancients. Will modern firearms protect

them? Or is the power of the timeless monster too great to overcome? Read my

story to find out.

Warren Bell is an author of historical fiction. He spent 29 years as a

US Naval Officer, and has traveled to most of the places in the world

that he writes about. A long-time World War II-buff, his first two

novels, Fall Eagle One and Hold Back the Sun are set during World War II. His third novel, Asphalt and Blood, follows the US Navy Seabees in Vietnam. His most recent novel, Snowflakes in July, was

released on Kindle on September 15, 2015, and a paperback version will

be following. For more about Warren Bell, visit his website at:

wbellauthor.com or see him on twitter @wbellauthor.

Warren Bell is an author of historical fiction. He spent 29 years as a

US Naval Officer, and has traveled to most of the places in the world

that he writes about. A long-time World War II-buff, his first two

novels, Fall Eagle One and Hold Back the Sun are set during World War II. His third novel, Asphalt and Blood, follows the US Navy Seabees in Vietnam. His most recent novel, Snowflakes in July, was

released on Kindle on September 15, 2015, and a paperback version will

be following. For more about Warren Bell, visit his website at:

wbellauthor.com or see him on twitter @wbellauthor.

Warren Bell is an author of historical fiction. He spent 29 years as a

US Naval Officer, and has traveled to most of the places in the world

that he writes about. A long-time World War II-buff, his first two

novels, Fall Eagle One and Hold Back the Sun are set during World War II. His third novel, Asphalt and Blood, follows the US Navy Seabees in Vietnam. His most recent novel, Snowflakes in July, was

released on Kindle on September 15, 2015, and a paperback version will

be following. For more about Warren Bell, visit his website at:

wbellauthor.com or see him on twitter @wbellauthor.

Warren Bell is an author of historical fiction. He spent 29 years as a

US Naval Officer, and has traveled to most of the places in the world

that he writes about. A long-time World War II-buff, his first two

novels, Fall Eagle One and Hold Back the Sun are set during World War II. His third novel, Asphalt and Blood, follows the US Navy Seabees in Vietnam. His most recent novel, Snowflakes in July, was

released on Kindle on September 15, 2015, and a paperback version will

be following. For more about Warren Bell, visit his website at:

wbellauthor.com or see him on twitter @wbellauthor.